The title of this post is the title of the last chapter of Jonathan Haidt’s 2012 book, The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion. It’s a question I’ve wondered a lot about. Liberals are doing the work needed to dismantle the powerful, yet subtle vestiges of inequality, exploitation, and repression. The struggle for the good society in which individuals are equal and free to pursue their own self-defined happiness is the one mission truly worth dedicating one’s life to achieving. Conservatives on the other hand wish to regain their way of life from those who sought to undermine it. They think that liberals are subverting traditional American values. Instead of requiring that people work for a living, liberals want to siphon money from hardworking Americans and gave it to drug addicts and welfare queens. Instead of punishing criminals, liberals tried to understand them. Liberals encourage a feminist agenda that undermined traditional family roles. Conservatives with to conserve values that they hold sacred. Jonathan Haidt is a social psychologist. In The Righteous Mind, he does an outstanding job of analyzing different principles of moral psychology. He explains how our righteous minds have made it possible for human beings - but no other animals - to produce large cooperative groups, tribes, and nations without the glue of kinship. But at the same time, our righteous minds guarantee that our cooperative groups will always be cursed by moralistic strife. Some degree of conflict among groups may even be necessary for the health and development of any society. There are a lot of good ideas from The Righteous Mind and I highly recommend the book to anyone interested in understanding how moral intuitions guide human nature. In this post I’m going to focus on his Moral Foundations Theory and the left’s blind spot: Moral Capital. Haidt opens chapter 6: Taste Buds of The Righteous Mind, with a story. He once visited a restaurant called True Taste. Each table was set only with five small spoons. He sat down at his table and looked at the menu. It was divided into sections labeled “Sugars," “Honeys,” “Tree Saps,” and “Artificials.” He called the waiter over and asked him to explain. Did they not serve food? The waiter told him that the restaurant was the first of its kind in the world: it was a tasting bar for sweeteners. Customers could sample sweeteners from thirty-two countries. The waiter then explained how he was actually a biologist who specialized in the sense of taste. He described the five kinds of taste receptor found in each taste bud on the tongue - sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and savory. He said that in his research he had discovered the activation of the sweet receptor produced by the strongest surge of dopamine in the brain, which indicated to him that humans are hard-wired to seek sweetness above the other four tastes. He therefore reasoned that it was most efficient, in terms of units of pleasure per calorie, to consume sweeteners, and he conceived the idea of opening a restaurant aimed entirely at stimulating this one taste receptor. Haidt asked him how business was going. “Terrible,” he said, “but at least I’m doing better than thechemist down the street who opened a salt-tasting bar.” The story didn’t really happen, but it’s a metaphor for how Haidt sometimes feels when he reads about moral philosophy and psychology. Morality is so complex. There are some who rise to the challenge, offering theories that try to explain moral diversity within and across cultures. Yet others reduce morality to a single principle, usually some variant of welfare maximization (i.e., help people, don’t hurt them). Sometimes it’s justice related, or about notions of fairness. There’s the Utilitarian Grill, catering welfare, and the Deontological Diner, serving only rights. This is moral monism - an attempt to ground all morality on a single principle. Haidt claims that this leads to societies that are unsatisfying to most people in it and at high risk of becoming inhumane because they ignore so many other moral principles. Humans all have the same five taste receptors, but we don’t all like the same foods. To understand where these differences come from, we can look at the evolutionary story about sugary fruits and fatty animals, which were good food for our common ancestors. But we’ll also have to examine the history of each culture, as well as the childhood eating habits of each individual. Just knowing that everyone has sweetness receptors can’t tell us why one person prefers Thai food to Mexican, or why anyone puts sugar in their beer. It’s the same for moral judgements. To understand why people are so divided by moral issues, we can start with an exploration of our common evolutionary heritage. But we’d also have to examine the history of each culture and the childhood socialization of each individual within that culture. Haidt develops an analogy inspired from David Hume’s work that that the righteous mind is like a tongue with six taste receptors. In this analogy, morality is like a cuisine. Cuisines vary, but they all must please tongues equipped with the same five taste receptors. Moral matrices also vary, but they all must please righteous minds equipped with the same six social receptors. Unfortunately in the decades after Hume’s death in 1776, the rationalists claimed victory over religion and took moral science off onto a two-hundred year tangent. It’s risky in the social sciences to assert that anything about human behavior is innate. To back up such claims, you’d have to show the trait was hardwired, unchangeable by experience, and found in all cultures. With that definition, not much is innate. We’ve come a long with in our understanding of the brain, and now know that traits can be innate without being hardwired or universal. Neuroscientist Gary Marcus explains that “nature bestows upon the newborn a considerably complex brain, but one that is best seen as prewired - flexible and subject to change - rather than hardwired, fixed, and immutable.” Marcus describes the brain like a book, the first draft of which is written by the genes during fetal development. No chapters are complete at birth, and some are just outlines waiting to be filled in during childhood. Not a single chapter - language, food preference, sexuality, or morality - consists of blank pages on which a society can inscribe any conceivable set of words. Nature provides a first draft, which experience then revises. With this definition, Haidt claims that moral foundations are innate. His theory proposes six of these foundations:

- Care/Harm - evolved in response to the adaptive challenge of caring for vulnerable children. It makes us sensitive to signs of suffering and need. It makes us despise cruelty and want to care for those who are suffering.

- Liberty/Oppression - a later addition, which makes people notice and resent any sign of attempted domination. It triggers an urge to band together to resist or overthrow bullies and tyrants. This foundation supports the egalitarianism and antiauthoritarianism of the left, as well as the don’t-tread-on-me and give-me-liberty antigovernment anger of libertarians and some conservatives.

- Fairness/Cheating - evolved in response to the adaptive challenge of reaping the rewards of cooperation without getting exploited. It makes us sensitive to indications that another person is likely to be a good (or bad) partner for collaboration and reciprocal altruism. It makes us want to shun or punish cheaters.

- Loyalty/Betrayal - evolved in response to the adaptive challenge of forming and maintaining coalitions. It makes us sensitive to signs that another person is (or is not) a team player. It makes us trust and reward such people, and it makes us want to hurt, ostracize, or even kill those who betray us or our group.

- Authority/Subversion - evolved in response to the adaptive challenge of forging relationships that will benefit us within social hierarchies. It makes us sensitive to signs of rank or status, and to signs that other people are (or are not) behaving properly, given their position.

- Sanctity/Degradation - evolved initially in response to the challenge of living in a world of pathogens and parasites, it includes the behavioral immune system, which can make us wary of a wide array of symbolic objects and threats. Sanctity/Degradation makes it possible for people to invest objects with irrational and extreme values - both positive and negative - which are important for binding groups together.

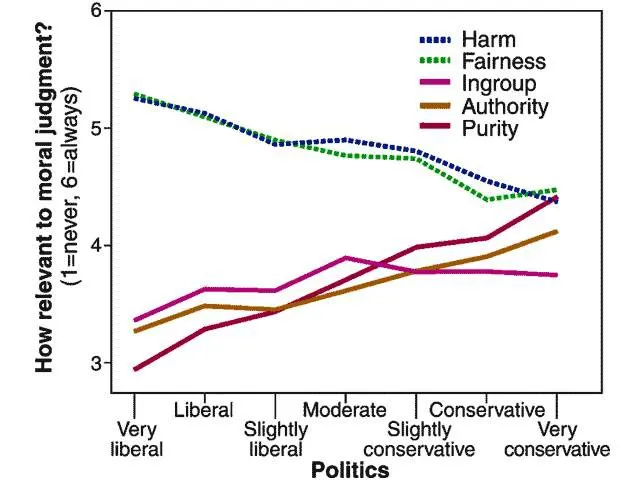

Moral Foundations Theory says that there are (at least) six psychological systems that comprise the universal

foundations of the world’s many moral matrices. The MFQ shows that the various moralities found on the political left

tend to rest most strongly on the Care/Harm and Liberty/Oppression foundations. These two foundations support ideals of

social justice, which emphasize compassion for the poor and a struggle for political equality among the subgroups that

comprise society. Social justice movements emphasize solidarity - they call for people to come together to fight the

oppression of bullying, domineering elites.

Everyone cares about Care/Harm, but liberals care more. Across many scales, surveys, and political controversies,

liberals turn out to be more disturbed by signs of violence and suffering, compared to conservatives and especially to

libertarians.

Everyone cares about Liberty/Oppression, but each political faction cares in a different way. In the United States, liberals are most concerned about the rights of certain vulnerable groups (i.e., racial minorities, children, animals),

and they look to government to defend the weak against oppression by the strong. Conservatives, in contrast, hold ideas of liberty such as the right to be left alone, and they often resent liberal programs that use government to infringe on their liberties in order to protect the groups that liberals care most about. For example,

small business owners overwhelmingly support the Republican Party in part because they resent the government telling

them how to run their businesses under its banner of protecting workers, minorities, consumers, and the environment.

This helps explain why libertarians have sided with the Republican Party in recent decades. Libertarians care about

liberty almost to the exclusion of all other concerns, and their conception of liberty is the same as that of the

Republicans: it is the right to be left alone, free from government interference.

Fairness/Cheating is about proportionality and the law of karma. It is about making sure that people get what they deserve, and do not get things they do not deserve. Everyone cares about proportionality; we get angry when

people take more than they deserve. But conservatives care more, and they rely on the Fairness foundation more heavily - until fairness is restricted to proportionality. For example, how relevant is it to your morality whether everyone is pulling their own weight? Do you agree that employees who work the hardest should be paid the most? Liberals don’t

reject these items, but they are ambivalent. Conservatives, in contrast, endorse these items enthusiastically.

Liberals may think that they own the concept of karma because of its New Age associations, but a morality based on compassion and concerns about oppression forces you to violate karma (proportionality) in many ways. Conservatives, for

example, think it’s self-evident that responses to crime should be based on proportionality, as shown in slogans such as

“do the crime, do the time.” Yet liberals are often uncomfortable with the negative side of karma - retribution. After

all, retribution causes harm. A recent study even found that liberal professors give out a narrower range of grades than

do conservative professors. Conservative professors are more willing to reward the best students and punish the worst.

The remaining three foundations - Loyalty/Betrayal, Authority/Subversion, and Sanctity/Degradation - show the biggest

and most consistent partisan differences. Liberals are ambivalent about these foundations at best, whereas social

conservatives embrace them. (Libertarians have little use for them, which is why they tend to support liberal positions

on social issues such as gay marriage, drug use, and laws to “protect” the American Flag).

Liberals have a three-foundation morality, whereas conservatives use all six. Liberal moral matrices rest on the

Care/Harm, Liberty/Oppression, and Fairness/Cheating foundations, although liberals are often willing to trade away

fairness (as proportionality) when it conflicts with compassion or with their desire to fight oppression. Conservative

morality rests on all six foundations, although conservatives are more willing than liberals to sacrifice care and let

some people get hurt in order to achieve their many other moral objectives.

The term social capital swept through the social sciences in the 1990s. There’s financial capital (money in the bank),

physical capital (a wrench or a factory), and human capital (a well-trained team). With everything equal, a company with

more of any kind will outcompete a firm with less. Social capital refers to the kind of capital that economists have

largely overlooked - the social ties among individuals and the norms of reciprocity and trustworthiness that come from

those ties. Markets today that require very high trust to function efficiently, such as the diamond market, are often

dominated by religiously bound ethnic groups, such as Orthodox-Jews, who have lower transaction and monitoring costs

than their secular competitors. This group’s social capital enables them to create the most efficient market because there’s less overhead on every transaction.

Let’s broaden our focus beyond firms trying to produce goods and think about a

school, community, or even nation wanting to improve their moral behavior. To achieve almost any moral vision, you’d

probably want high levels of social capital. It’s hard to imagine how distrust could be beneficial. But is linking

people together into healthy, trusting relationships enough to improve the ethical profile of the group?

If you believe that people are inherently good, and that they flourish when constraints and divisions are removed, then

yes, that may be sufficient. But conservatives generally take a very different view of human nature. They believe that

people need external structures or constraints in order to behave well, cooperate, and thrive. These external

constraints include laws, institutions, customs, traditions, nations, and religions. Without them, people will begin to

cheat and behave selfishly. Without them, social capital will rapidly decay.

For liberals, their eyes tend to fall on individual objects such as people, and they don’t automatically see the

relationships among them. Having a concept such as social capital is helpful because it forces us to see the

relationships within which those people are embedded, and which make those people more productive. But to understand the

miracle of moral communities that grow beyond the bounds of kinship we must look not just at people, and not just at the

relationships among people, but at the complete environment within which those relationships are embedded, and which

makes those people more virtuous (however they themselves define that term). It takes a great deal of outside-the-mind stuff to support a moral community.

Haidt defines moral capital as that stuff. Moral capital are the resources that sustain a moral community. Specifically, it refers to “the degree to which a community possesses interlocking sets of values, virtues, norms, practices,

identities, institutions, and technologies that mesh well with evolved psychological mechanisms and thereby enable the

community to suppress or regulate selfishness and make cooperation possible.”

If you're trying to change an organization and you do not consider the effects of your changes on moral capital, you’re asking for trouble. Haidt believes this is the fundamental blind spot of the left. It explains why

liberal reforms so often backfire and why communist revolutions usually end up in despotism. It is the reason liberalism

- which has done so much to bring about freedom and equal opportunity - is not sufficient as a governing philosophy. It

tends to overreach, change too many things too quickly, and inadvertently reduce the stock of moral capital. Conversely,

while conservatives do a better job of preserving moral capital, they often fail to notice certain classes of victims,

fail to limit the predations of certain powerful interests, and fail to see the need to change or update institutions as times change. Once people join a political team, they get ensnared in its moral matrix. They see confirmation of their grand narrative

everywhere, and it’s difficult - perhaps impossible - to convince them that they are wrong if you argue with them from outside of their matrix.

Liberals have a harder time understanding conservatives than the other way around, because liberals often have difficulty understanding how the Loyalty, Authority, and Sanctity foundations have anything to do with morality. In particular, liberals often have difficulty seeing moral capital - the resources that sustain a moral community. That being said, Liberals are experts in care; they are better able to see the victims of existing social arrangements, and

they continually push us to update those arrangements and invent new ones. This moral matrix leads liberals to make two

points that are important for the health of a lasting society: 1. governments can and should restrain corporate super organisms, and 2. some big problems really can be solved by regulation.

Liberals and conservatives are like yin and yang - both necessary elements of a healthy state of political life. A nationstate is in trouble when one ideology dominates and leaves no room for nuance, which is where I fear the United

States could be headed. I would love to see a world where competing ideologies are kept in balance and fewer people believe that righteous ends justify violent means. I believe that's the only way we sustain humanity in the long run.

Moral Foundations Theory says that there are (at least) six psychological systems that comprise the universal

foundations of the world’s many moral matrices. The MFQ shows that the various moralities found on the political left

tend to rest most strongly on the Care/Harm and Liberty/Oppression foundations. These two foundations support ideals of

social justice, which emphasize compassion for the poor and a struggle for political equality among the subgroups that

comprise society. Social justice movements emphasize solidarity - they call for people to come together to fight the

oppression of bullying, domineering elites.

Everyone cares about Care/Harm, but liberals care more. Across many scales, surveys, and political controversies,

liberals turn out to be more disturbed by signs of violence and suffering, compared to conservatives and especially to

libertarians.

Everyone cares about Liberty/Oppression, but each political faction cares in a different way. In the United States, liberals are most concerned about the rights of certain vulnerable groups (i.e., racial minorities, children, animals),

and they look to government to defend the weak against oppression by the strong. Conservatives, in contrast, hold ideas of liberty such as the right to be left alone, and they often resent liberal programs that use government to infringe on their liberties in order to protect the groups that liberals care most about. For example,

small business owners overwhelmingly support the Republican Party in part because they resent the government telling

them how to run their businesses under its banner of protecting workers, minorities, consumers, and the environment.

This helps explain why libertarians have sided with the Republican Party in recent decades. Libertarians care about

liberty almost to the exclusion of all other concerns, and their conception of liberty is the same as that of the

Republicans: it is the right to be left alone, free from government interference.

Fairness/Cheating is about proportionality and the law of karma. It is about making sure that people get what they deserve, and do not get things they do not deserve. Everyone cares about proportionality; we get angry when

people take more than they deserve. But conservatives care more, and they rely on the Fairness foundation more heavily - until fairness is restricted to proportionality. For example, how relevant is it to your morality whether everyone is pulling their own weight? Do you agree that employees who work the hardest should be paid the most? Liberals don’t

reject these items, but they are ambivalent. Conservatives, in contrast, endorse these items enthusiastically.

Liberals may think that they own the concept of karma because of its New Age associations, but a morality based on compassion and concerns about oppression forces you to violate karma (proportionality) in many ways. Conservatives, for

example, think it’s self-evident that responses to crime should be based on proportionality, as shown in slogans such as

“do the crime, do the time.” Yet liberals are often uncomfortable with the negative side of karma - retribution. After

all, retribution causes harm. A recent study even found that liberal professors give out a narrower range of grades than

do conservative professors. Conservative professors are more willing to reward the best students and punish the worst.

The remaining three foundations - Loyalty/Betrayal, Authority/Subversion, and Sanctity/Degradation - show the biggest

and most consistent partisan differences. Liberals are ambivalent about these foundations at best, whereas social

conservatives embrace them. (Libertarians have little use for them, which is why they tend to support liberal positions

on social issues such as gay marriage, drug use, and laws to “protect” the American Flag).

Liberals have a three-foundation morality, whereas conservatives use all six. Liberal moral matrices rest on the

Care/Harm, Liberty/Oppression, and Fairness/Cheating foundations, although liberals are often willing to trade away

fairness (as proportionality) when it conflicts with compassion or with their desire to fight oppression. Conservative

morality rests on all six foundations, although conservatives are more willing than liberals to sacrifice care and let

some people get hurt in order to achieve their many other moral objectives.

The term social capital swept through the social sciences in the 1990s. There’s financial capital (money in the bank),

physical capital (a wrench or a factory), and human capital (a well-trained team). With everything equal, a company with

more of any kind will outcompete a firm with less. Social capital refers to the kind of capital that economists have

largely overlooked - the social ties among individuals and the norms of reciprocity and trustworthiness that come from

those ties. Markets today that require very high trust to function efficiently, such as the diamond market, are often

dominated by religiously bound ethnic groups, such as Orthodox-Jews, who have lower transaction and monitoring costs

than their secular competitors. This group’s social capital enables them to create the most efficient market because there’s less overhead on every transaction.

Let’s broaden our focus beyond firms trying to produce goods and think about a

school, community, or even nation wanting to improve their moral behavior. To achieve almost any moral vision, you’d

probably want high levels of social capital. It’s hard to imagine how distrust could be beneficial. But is linking

people together into healthy, trusting relationships enough to improve the ethical profile of the group?

If you believe that people are inherently good, and that they flourish when constraints and divisions are removed, then

yes, that may be sufficient. But conservatives generally take a very different view of human nature. They believe that

people need external structures or constraints in order to behave well, cooperate, and thrive. These external

constraints include laws, institutions, customs, traditions, nations, and religions. Without them, people will begin to

cheat and behave selfishly. Without them, social capital will rapidly decay.

For liberals, their eyes tend to fall on individual objects such as people, and they don’t automatically see the

relationships among them. Having a concept such as social capital is helpful because it forces us to see the

relationships within which those people are embedded, and which make those people more productive. But to understand the

miracle of moral communities that grow beyond the bounds of kinship we must look not just at people, and not just at the

relationships among people, but at the complete environment within which those relationships are embedded, and which

makes those people more virtuous (however they themselves define that term). It takes a great deal of outside-the-mind stuff to support a moral community.

Haidt defines moral capital as that stuff. Moral capital are the resources that sustain a moral community. Specifically, it refers to “the degree to which a community possesses interlocking sets of values, virtues, norms, practices,

identities, institutions, and technologies that mesh well with evolved psychological mechanisms and thereby enable the

community to suppress or regulate selfishness and make cooperation possible.”

If you're trying to change an organization and you do not consider the effects of your changes on moral capital, you’re asking for trouble. Haidt believes this is the fundamental blind spot of the left. It explains why

liberal reforms so often backfire and why communist revolutions usually end up in despotism. It is the reason liberalism

- which has done so much to bring about freedom and equal opportunity - is not sufficient as a governing philosophy. It

tends to overreach, change too many things too quickly, and inadvertently reduce the stock of moral capital. Conversely,

while conservatives do a better job of preserving moral capital, they often fail to notice certain classes of victims,

fail to limit the predations of certain powerful interests, and fail to see the need to change or update institutions as times change. Once people join a political team, they get ensnared in its moral matrix. They see confirmation of their grand narrative

everywhere, and it’s difficult - perhaps impossible - to convince them that they are wrong if you argue with them from outside of their matrix.

Liberals have a harder time understanding conservatives than the other way around, because liberals often have difficulty understanding how the Loyalty, Authority, and Sanctity foundations have anything to do with morality. In particular, liberals often have difficulty seeing moral capital - the resources that sustain a moral community. That being said, Liberals are experts in care; they are better able to see the victims of existing social arrangements, and

they continually push us to update those arrangements and invent new ones. This moral matrix leads liberals to make two

points that are important for the health of a lasting society: 1. governments can and should restrain corporate super organisms, and 2. some big problems really can be solved by regulation.

Liberals and conservatives are like yin and yang - both necessary elements of a healthy state of political life. A nationstate is in trouble when one ideology dominates and leaves no room for nuance, which is where I fear the United

States could be headed. I would love to see a world where competing ideologies are kept in balance and fewer people believe that righteous ends justify violent means. I believe that's the only way we sustain humanity in the long run.